Fool’s Template Injection

Table of Contents

Introduction#

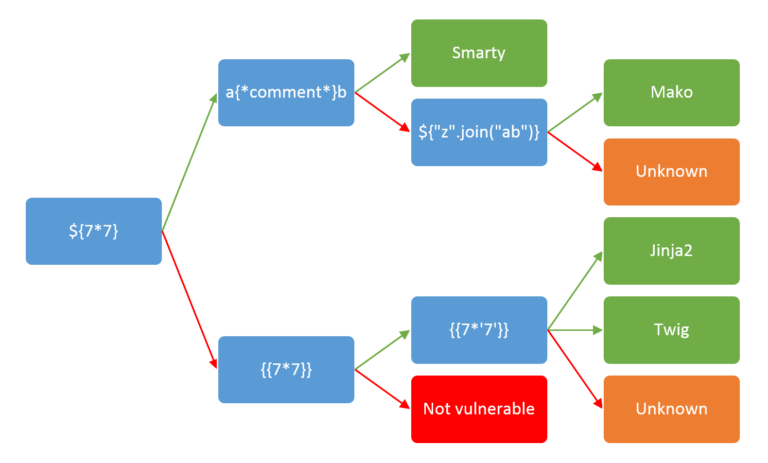

Imagine you are conducting a standard penetration test against an older web application. After making sure the credentials you were provided with work, you start spamming payloads into every input field you can find. Single quotes? Nothing happens. HTML tags? Filtered. {{7*7}}? Nothing happens 49?!?. You can’t believe your luck - you’ve hit the jackpot! You quickly pull up this flowchart, and try to determine the exact payload you need to get a reverse shell on the site.

Unfortunately, after trying three or four payloads you realize the results contradict each other, and you start to doubt yourself.

This is more or less what happened to me on a recent pentest. I thought I had discovered a typical server-side template injection, when in reality I ran into a weird client-side template injection. “Fool’s Gold” of the penetration testing world… In an instant, the RCE I allowed myself to get so excited about had been knocked down to an XSS.

Server-Side Template Injection#

So, what’s the difference? And for those readers who may not be as familiar - what am I even talking about? Many websites nowadays make use of various templating engines. This allows them to use static template files for web pages containing variables which can be updated at runtime by the templating engine. Server-side template injection is a type of vulnerability where an attacker is able to inject template code into a page before it is rendered. The possibilities for exploitation are numerous, as templating engines often allow developers to execute arbitrary code on the server.

A template might look like this on the server-side:

1<!DOCTYPE html>

2<html>

3 <body>

4 <h1>Hi, {{ user.username }}!</h1>

5 </body>

6</html>

And like this, when rendered:

1<!DOCTYPE html>

2<html>

3 <body>

4 <h1>Hi, pentestuser!</h1>

5 </body>

6</html>

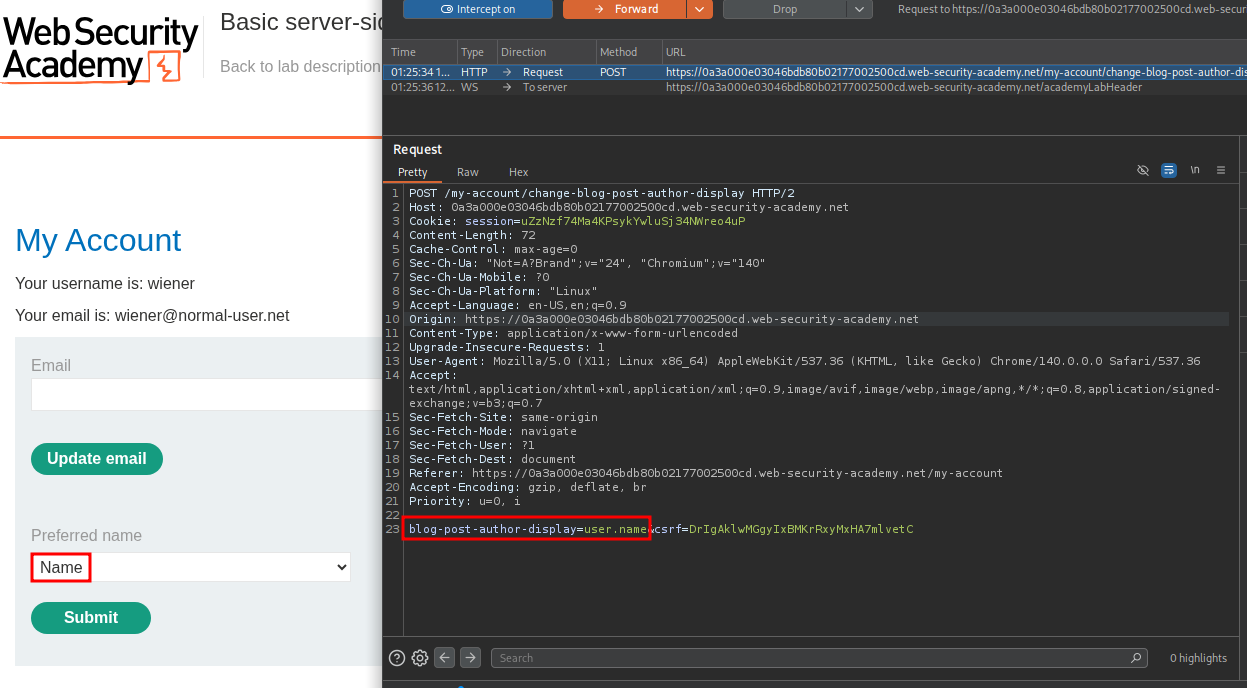

Take this web app from PortSwigger’s Academy, for example. Once logged in, users may select a prefered way to be called by - username, firstname, or nickname. In the requests sent to the backend, this translates to user.name, user.first_name, and user.nickname.

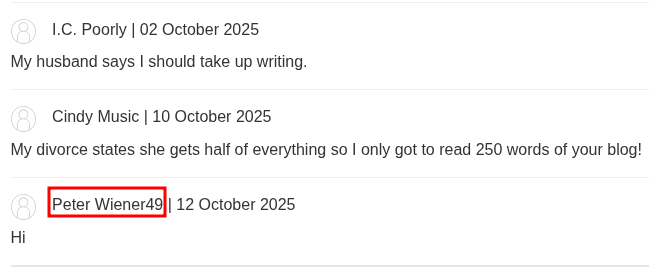

With some trial and error, it is discovered that these are the variables being used in the backend template, which looks something like: {{user.name}}. By adding some curly braces of our own, it is possible break out of the original expression, and add additional code to be evaluated on the server-side. For example, by setting blog-post-author-display to user.name}}{{7*7, we suddenly appear as Peter Wiener49 in the comments, since the templating engine is now evaluating {{user.name}}{{7*7}}.

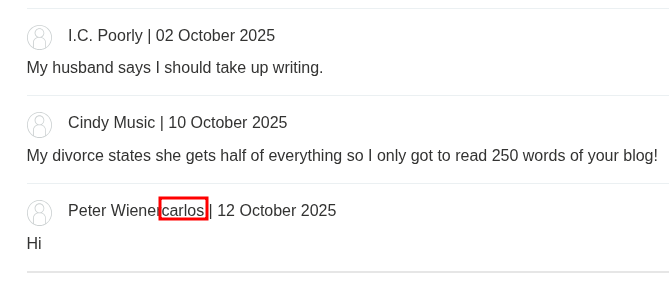

In this case, the web application was developed in Python, and uses the Tornado templating engine. With a very minimal amount of googling, syntax for executing shell commands in Python can be discovered, and the payload can be adapted accordingly to one that displays the user the webserver is running as: user.name}}{% import os %}{{ os.popen("whoami").read().

At this point, we’ve already demonstrated remote-code execution on the server as carlos. In a real engagement, depending on the scope, we might either stop here, or continue by getting a reverse shell and attempting to escalate privileges on the server.

Client-Side Template Injection#

Client-side template injection is a similar type of vulnerability, in that an attacker injects code into a template before it is rendered. The difference, however, is that template rendering happens in the client’s browser, and so the potential impact is much more limited.

Although it is no longer supported, take the following AngularJS code, as an example.

1...SNIP

2<div ng-app>

3 Hi, {{ user.username }}!

4</div>

5...

Once rendered, it might look like this:

1...SNIP...

2<div ng-app="" class="ng-binding ng-scope">

3 Hi, pentestuser!

4</div>

5...SNIP...

As you’ve surely noticed, the template syntax {{ ... }} is the same. In my case, the {{7 * 7}} that I entered was somehow getting into the template and thus evaluated. Getting an XSS out of this was relatively easy - it only required getting past their “HTML filter”, but it certainly had me perplexed for a good 15 minutes…

Conclusion#

AngularJS hasn’t been supported since 2022. You might still run into it, as I did, but modern websites using modern Angular are much more difficult to exploit, due to variable context, HTML sanitization, and other measures. Client-side templating engines are becoming increasingly “secure by default”, and it’s quite difficult to introduce XSS vulnerabilities into a web app, unless you go out of your way to use functions with scary names like bypassSecurityTrustHtml…